I know that one of the symptoms of aging is spending time looking back and remembering how it was in the old days. Bruce Springsteen noted that “time slips away and leaves you with nothing … but boring stories of glory days.” So, I apologize for this, but hearing today about the death of Neil Armstrong really set my mind to wandering. From 1968-1970 I worked in the Chemistry Department at UW-Madison with Dr. Larry Haskin and his graduate students. I started working with this group after receiving a National Science Foundation Undergraduate Research Program grant. When the grant ended I continued to work for him while being paid as a student lab assistant.

Dr. Haskin was one of the principal investigators for NASA and he was selected to receive samples of “moon rocks” from Apollo 11 and 12. In preparation for this I worked with one of his grad students, Ralph Allen, who was developing a process for analyzing lunar materials for rare earth and other trace elements. The process involved irradiating the samples in a nuclear reactor, dissolving them and separating the elements into various constituent groups using traditional wet chemical methods, and then analyzing the radiation emitted by the elements by Neutron Activation. (There was much more to it than that but I am trying to go easy on the boring part.)

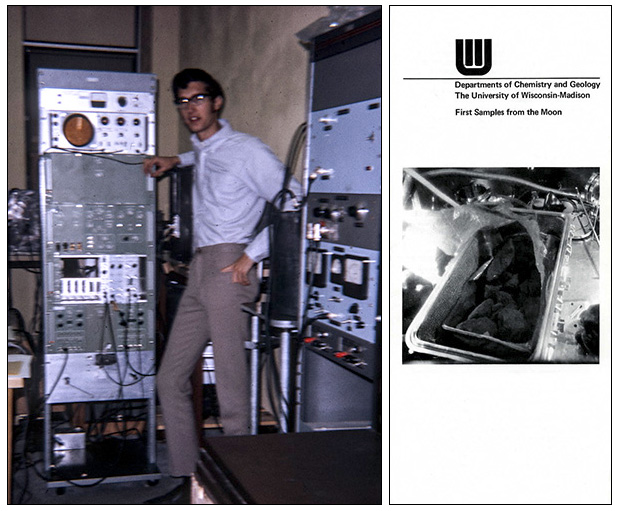

The blurry picture below on the left was taken of me in the spring of 1969 while analyzing some samples (not from the moon yet) using a scintillation detector. Since some of you are probably wondering about this, let me point out that the detector we used was a germanium (Ge) crystal with small amounts of lithium (Li) dispersed throughout. I mention this because this was usually denoted as a Ge(Li) detector. And yes Virginia, it was called a “jelly” detector.

As you can imagine, when I watched Neil Armstrong step out onto the surface of the moon I was amazed and overjoyed that the US had made it there safely and couldn’t believe that I would soon be working with a group of scientists to analyze what the astronauts would bring back. When we finally received the samples the first thing that the University did was set up a well-guarded display in the Chemistry Building so that the public could file through and see these very first samples brought back to earth from the moon. The picture on the right above is the cover of the brochure that was handed out to the people who came to see these samples. I still have a couple of them along with copies of research papers that discussed the results of this research. If you’d like to read the brochure, I made a PDF file that you can download here.

If any of you are still here, thanks for letting me present this boring story of glory days.

PS — After Ralph Allen got his PhD he went to the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He’s still there. Dr. Haskin moved to Houston where he headed the Planetary and Earth Sciences Division at the NASA Johnson Space Center for several years and then went on to Washington University in St. Louis. He died in 2005 from a disease of the bone marrow. It’s interesting to note that in 2009 the International Astronomical Union named one of the craters on the moon for Dr. Haskin.