I know that I’ve told this story before so please pardon my repetition. With all of the 50th anniversary stories about Apollo 11 on the news and in the papers I feel that I should be allowed to mention my very small connection to this event. After marrying Kathy and having two wonderful sons, this is one of the more memorable things in my life.

– – – – –

In the summer of 1968, after my sophomore year in college, I received a National Science Foundation Undergraduate Research Program Grant. Since I was interested in analytical chemistry, I opted to work with Dr. Larry A. Haskin’s research group in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Chemistry Department. The analytical technique Dr. Haskin specialized in was neutron activation analysis, a method that involves bombarding a sample with neutrons in a nuclear reactor and measuring the gamma rays emitted by the irradiated sample. Since different elements emit gamma rays at different energy levels, specific elements can be measured from within a complex mixture. This method is quite sensitive and can be used to analyze mineral samples for rare earth and other trace elements. The grant paid $60 a week tax-free and, at twenty years old, I felt like a rich man.

When the term of the grant ended in the fall of 1968, Dr. Haskin hired me to work with one of his graduate students, Ralph Allen, who was developing a procedure for using neutron activation to analyze the composition of small geologic samples. Dr. Haskin was one of the Principal Investigators for NASA and the goal was to use this method to analyze lunar samples collected during the Apollo 11 mission. Ralph was doing the research for his PhD; I was just an undergrad assisting him with some of the chemistry. I earned $1.10 an hour, not tax-free, and felt more like a lower-middle-class man.

In the summer of 1969, the work on the project with Ralph was getting rather exciting. We had carried out a number of test runs to ensure the efficacy of the procedure and to hone our skills with the variety of chemical separations needed for the analytical scheme. The launch of Apollo 11 took place on the morning of Wednesday, July 16. You’d think I would have remained glued to the TV during the entire mission. But, some of my family members had scheduled their vacation for the week after the launch, so Kathy and I drove up to join them on Washington Island, which sits at the tip of the Door County Peninsula in Wisconsin. There were no televisions in the cottages that we rented so it seemed unlikely that we would be able to view any of the events that would be taking place 239,000 miles away on the surface of the moon.

The landing was scheduled for Sunday, July 20. That evening we drove to our favorite bar, a place we called “The Bitters Bar.” Bars didn’t have TVs covering the walls in those days so we didn’t go there to watch news of the landing. My brother-in-law knew the owner of the bar and asked him where we might be able to find a television. He told us we could watch the TV at his house.

The “Eagle” had already landed when we began to watch the broadcast. I remember a small group of people sitting for several hours waiting anxiously and somewhat impatiently for the astronauts to emerge. Neil Armstrong finally stepped out and I suspect that I held my breath. Despite the poor reception on the small black-and-white screen, the image of him slowly stepping onto the surface of the moon remains clear in my mind. I don’t remember if I cheered or just sat there in quiet awe, but fifty years later Apollo 11 still flies in my memory.

Samples from Apollo 11 eventually arrived at the University. Some went to Dr. Haskin for trace element analysis and some went to another Principal Investigator for NASA, Dr. Eugene Cameron in the Geology Department, to be analyzed for mineralogy and bulk composition. Before any work was performed on the samples, the Departments of Chemistry and Geology arranged a public viewing of some of the samples. As you can imagine, it was a very popular event. I still have a copy of the brochure that we handed out to the visitors. If you’re interested in reading it, please click here to download a copy.

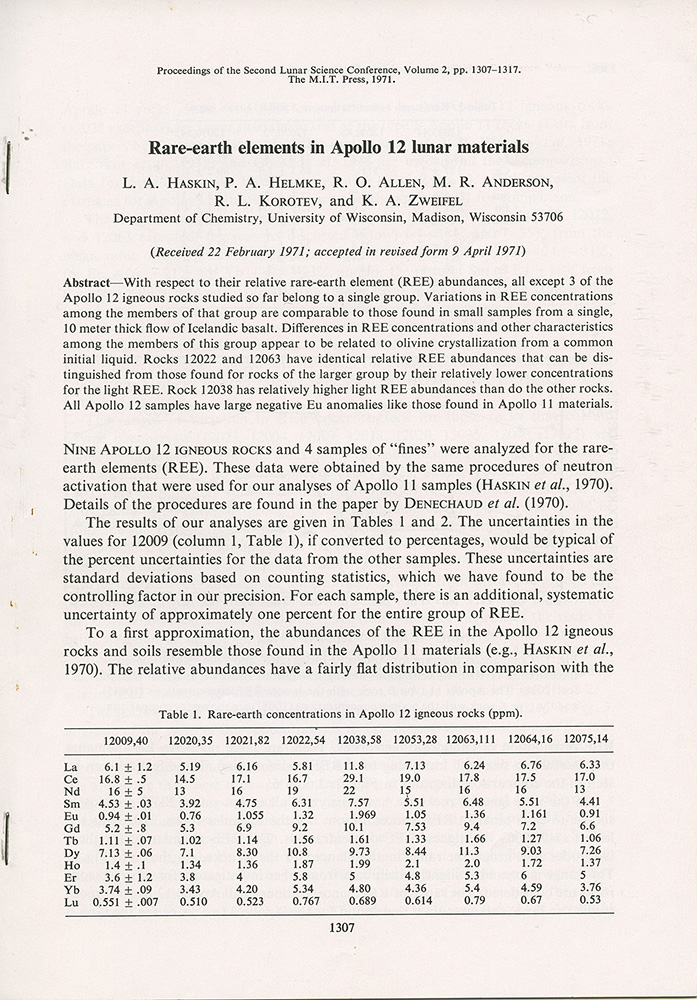

Dr. Haskin later received samples from Apollo 12 and I was fortunate to work with Ralph Allen on samples from both the Apollo 11 and 12 missions. After each sample was irradiated we carried out the neutron activation analysis around the clock. Since I only lived a few blocks from the chemistry building and was the low man in the team hierarchy, I made the middle-of-the-night-trips to change the samples that we were analyzing.

Many of you are probably wondering, is that a not-quite-21-year-old Mike Anderson in this photo? Yes, you’re right! I hired a young blond woman to take this picture with a Kodak Instamatic camera. The blur was added to confuse any facial recognition programs that might be invented in the future.

Many of you are also probably wondering, is that a lithium-drifted germanium gamma ray detector that you’re using in this photo? Yes, you’re right! But, instead of saying “lithium-drifted germanium gamma ray detector” we just called it a Ge(Li) detector, pronounced “jelly detector.” This was taken during some preliminary tests that we ran in the Spring of 1969. My phone was connected to a wire back in my Dayton Street apartment so I could not use it to photograph any of this work.

If I don’t stop typing now I’m afraid I’ll start getting into the chemistry which, though interesting to me, would surely put all of you to sleep. Instead of that I’ll just post the cover pages from a few of the publications from this work.

The publication above is the procedure that Ralph developed for the analyses. Note that the abstract says it takes 7 hours for 3 chemists to do the work. The majority of the chemical separation was carried out by two chemists, Ralph and me, working side by side in the sub-basement of the chemistry building. Since the samples were radioactive, we had to carry out much of the work in laboratory hoods while wrapping our arms around piles of lead bricks. We could see what we were doing by looking over the top of the bricks.

The publications above and below are, obviously, from the work on samples from Apollo 11 and Apollo 12.

Some post scripts:

Larry Haskin left the UW-Madison to head the Planetary and Earth Sciences Division at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. He later chaired the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. After his death the International Astronomical Union honored him by officially giving his name to a crater on the moon.

Ralph Allen was awarded his PhD from the UW-Madison and took a position at the University of Virginia where he still works today as an emeritus professor.

Thanks for letting me share some of my old moon memories.